Plotting and structure for cheats (or, how to gaff-tape your cardboard thingy)

I’ve banged on elsewhere about the themes that tie together some of the stories in my new collection, Angel Dust, such as my possibly neurotic obsession with the consequences of men failing to be “good men” and (possibly contrarily) my enduring fetish for shiny ladies with wings. There’s also a couple of fantasy worlds that I return to more than once through the book: an alternate Australia where the dreams of the land prey on people and your shadow won’t reliably stay under your feet; and an early steam age faux-Europe, where tax collectors and little girls turn out to be the ultimate bad asses.

I’ve banged on elsewhere about the themes that tie together some of the stories in my new collection, Angel Dust, such as my possibly neurotic obsession with the consequences of men failing to be “good men” and (possibly contrarily) my enduring fetish for shiny ladies with wings. There’s also a couple of fantasy worlds that I return to more than once through the book: an alternate Australia where the dreams of the land prey on people and your shadow won’t reliably stay under your feet; and an early steam age faux-Europe, where tax collectors and little girls turn out to be the ultimate bad asses.

Another thing that connects quite a number of the stories in the book is how they were written. In wrestling with the challenges of transitioning from being a “professional” short fiction writer to trying out as a novice novelist, I’ve discovered something about my writing.

What I’ve realised is that my writing has a number of strengths – I can do character, setting, action, dialogue, mood and tension fairly reliably. But, by comparison, I suck at story structure and plot. It’s like I have the full six-pack, but the cardboard thingy that holds it together has gotten soggy and if I don’t put my hand under it, all the receptacles of fermented goodness will fall out the bottom and smash on the path. In short stories, I think you can get by with being weaker on structure and plot if you’re strong enough on the rest, but even in short form it’s something I’ve needed to address.

Some stories just kind of fall out easily by themselves, like “The Wishwriter’s Wife”, which is reprinted in Angel Dust and made the Year’s Best Australian Fantasy and Horror. (It’s also archived online at Daily SF, where it first appeared, so you can try before you buy.) Mostly, though, I’ve realised I need a bit of help.

In high school, my mates had a saying, “Win if you can, lose if you must, but always remember to cheat.” So I’ve developed a number of tricks and tools (cheats) to prop up my plotting and structure – to gaff tape the cardboard thingy of my stories.

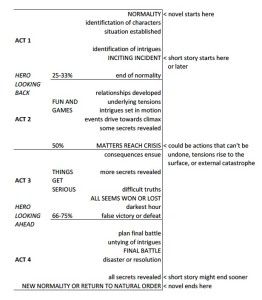

My first cheat is planning onto a formal act structure. I’ve adapted my own version, which largely follows the Hollywood 3-act / 4-part structure, but also borrows useful odds and ends from 2- and 5-act structures. Thus:

The main caveat here is that short stories almost never use the whole act structure. As a general rule of thumb, they should start no earlier than the ‘inciting incident’, that sets the hero on their journey, and get out as soon as possible after the story problems are resolved – or even as soon as the resolution is apparent.

I don’t always follow that formula by any means. In one of the stories in Angel Dust, I tell the first act and the fourth act and, in between, my protagonist sits on his roof and sulks for a few paragraphs while acts two and three rage below. Another story in the book takes place entirely within acts two and three of the structure, and in other stories I combine, skip or reverse some of the steps.

So, just because I start from a template, doesn’t mean I’m following it slavishly – and writing formulaically. But starting from the template really helps me think through a part of my writing that I’m weaker on.

Something I always do when I’m planning a story is a quick map of my characters’ emotional buttons – what they want, what they need, what they have to lose and what will hurt them the most. (Killing them, BTW, isn’t what will hurt your characters the most. It’s the Princes Bride Rule: “To The Pain!” What will hurt your characters most is not the thing that kills them, but the thing that leaves them alive and in freakish suffering.) Pushing my protagonist’s buttons – and often those of the antagonist and any other major characters – has to be at the heart of the story I tell.

My second cheat for plotting and structure is for generating an actual plot from those emotional buttons (along with whatever idea or conceit I’ve decided to write a story about). This one’s pretty simple: I start throwing random elements at them and see what sticks.

If my idea didn’t already come from a book, then one of those random elements is almost always a book (or magazine or Wikipedia page or somesuch). For the story “Cold, Cold War”, which is in Angel Dust and also archived at Beneath Ceaseless Skies (try before you buy!), it was a photographic history of the Russian Civil War that I found in a bookshop bargain bin. For “Beetle Road”, the opening story of Angel Dust, it was both an issue of National Geographic with a cover story on jewelled scarabs and a book on transcontinental railways that were in the pile on the table at the writers’ centre.

Another randomiser I often use is Georg Polti’s 36 Dramatic Situations. You can find them online here, complete with Random Dramatic Situation Generator and a bonus dramatic situation. I get the top-level situation randomly, then choose the sub-situation that I like the best. (Of all the various models of story archetypes, this is the most OCD – over 300 story ideas, right here!)

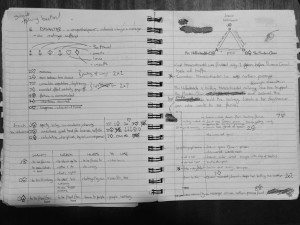

My other go-to randomisers are rolling Crown & Anchor dice (any dice will do but I like the pictures) and dealing playing cards to which I apply a tarot interpretation. Then I start associating cards and dice with characters and story events, sticking the characters onto a character triangle and filling in the events on my act structure.

Sometimes I’ll even generate whole stories from random elements, and use the playing cards to generate characters as well as events. “Beetle Road” is one of those, written for a 24-hour story challenge that I ran with my writers’ group, the Canberra Speculative Fiction Guild. “Uncle Bob’s Crocodile”, which is too new to be in Angel Dust, but which you can read at Urban Fantasy magazine, is another story that was generated entirely from (a simpler set of) random elements: a friend’s anecdote about his crazy uncle; a page from Luigi Seraphini’s Codex Seraphinianus; and a random object which I forgot about.

“Beetle Road” was the whole kit and kitchen sink – random books, random characters, Polti, dice, playing cards. So, without giving too much away (because only so much of my planning ever survives the actual process of writing, as you’ll see if you read the story) my plan for “Beetle Road” looked like this:

Of course, if you’re strong on plot, doing all of this for most stories would drive you nuts. But even if plot is one of your strengths, sometimes you’ll get stuck, and it’s good to have some cheats in your back pocket to help you get unstuck. And if you are like me and not so strong on plot, then over time doing all the stuff that comes from these tricks and tools becomes more and more second-nature, and sooner or later you’ll find you’ve got a pretty solid cardboard thingy to hold your six-pack together.

Ian McHugh’s debut short story collection, Angel Dust, was a finalist for this year’s Aurealis Awards (and is available here from Ticonderoga Publications). You can find more of his stories, which have appeared in professional and semi-pro magazines, webzines and anthologies in Australia and internationally, at his website. His stories have won grand prize in the Writers of the Future contest and been shortlisted five times at the Aurealis Awards, winning in 2010. He’s a graduate of Clarion West.

Ian McHugh’s debut short story collection, Angel Dust, was a finalist for this year’s Aurealis Awards (and is available here from Ticonderoga Publications). You can find more of his stories, which have appeared in professional and semi-pro magazines, webzines and anthologies in Australia and internationally, at his website. His stories have won grand prize in the Writers of the Future contest and been shortlisted five times at the Aurealis Awards, winning in 2010. He’s a graduate of Clarion West.

.